... but that's actually a good thing

I've already written a ton about subinterpreters since a year ago:

- How good are sub-interpreters in Python now?

- Python 3.14: State of free threading

- Subinterpreters and Asyncio

Recently I had some time to dig a bit deeper into subinterpreters and check my understanding of them.

Efficient data sharing between interpreters

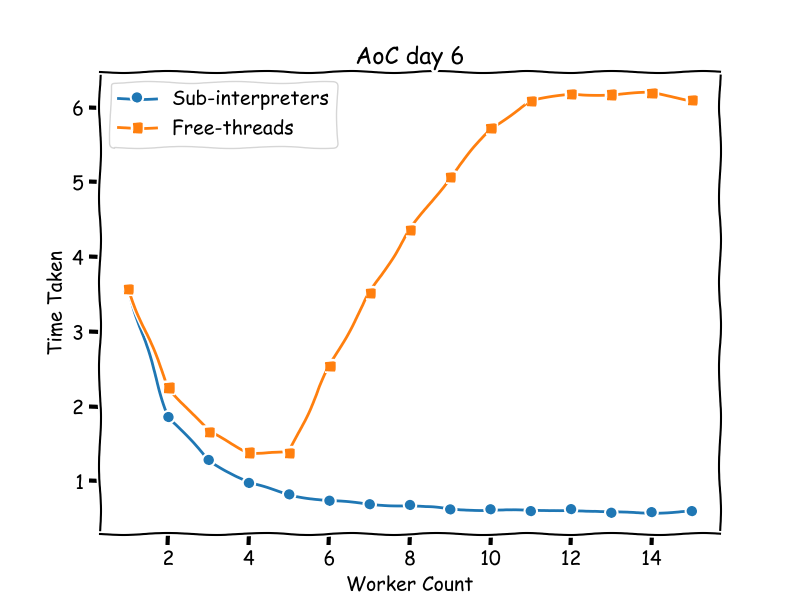

My first attempt at using it was to solve an Advent of Code. This involved running the same function around 4000 times on the same grid of values.

The function makes a lot of read only access to the grid, which causes high lock contention in a free-threaded implementation. But with interpreters the performance scaled pretty much perfectly. Here's a chart of the performance differences:

In the article I claimed:

There are also other ways to execute code I chose not to use like InterpreterPoolExecutor which don't take advantage of shared objects, or

Interpreter.callwhich places limitations on the function called.

But something didn't sit right with me, why would there not be an easy to use implementation for users?

So I gave it another look and reimplemented my solution with the standard executor here:

candidates = ((start, node, grid) for node in path if node != start)

with InterpreterPoolExecutor() as executor:

sum(1 for res in executor.map(solve, candidates) if res)

... and the results indeed came out a lot slower. Around 4 seconds compared to the 0.6 seconds before (13 threads on my M3 Macbook).

So that seems to prove my point then? Well not exactly, I tried rewriting my own implementation again like:

candidates = ((start, node, grid) for node in path if node != start)

executor = Executor("implementations.d6", "solve", workers=workers)

sum(1 for res in executor.map(solve) if res)

it was just as slow. So what's going on here?

It turns out that whether using the standard library or hand writing my own executor, we're both using the same 'sharing' mechanism to move the arguments and results in and out of the interpreter.

But I had assumed that when we shared the grid of type tuple[tuple[bool, ...], ...] we simply share the reference of the object. But this is not actually the case, the docs don't go into a lot of detail in actual fact, most objects are copied between interpreters.

This doesn't explain why my initial implementation was so fast. After rechecking my original code, I found out that I had gotten quite lucky and used interpreters.prepare_main to pass the grid to each interpreter at the start. This still perform the copy but only once for each worker, on the other hand, my newer implementations copy grid for each invocation.

To show this more clearly, we can use memoryview instead. memoryview is one of the few exceptions that do not require copying as it shares mutable data. The way it works is that the memoryview object itself is copied each time but the underlying data is simply referenced.

Changing the grid to a memoryview backed by a bytearray we get back our performance we expect. See the code below:

Efficient function passing

In Subinterpreters and Asyncio, I tried to make subinterpreters work more generally with asyncio and created aiointerpreters.

Here again I made some incorrect claims:

In order to pass the function itself, the arguments and return values are pickled before they are passed to the interpreters. Which will impact performance and may cancel out a lot of the performance gains over other parallelism mechanisms like free-threading and multi-processing.

Which as we know now, the only way to avoid copying the data is using memoryview or to reduce the amount of copying using something interpreters.prepare_main.

Another thing I got wrong is:

Then there's the problem of loading functions into the interpreters. As far as I can tell, the best way to do so without pickle is to import the functions inside the interpreters. This is likely the mechanism behind

call_in_thread.

At the time, I had not realised that pickle works on functions the following way:

Note that functions (built-in and user-defined) are pickled by fully qualified name, not by value. This means that only the function name is pickled, along with the name of the containing module and classes. Neither the function’s code, nor any of its function attributes are pickled. Thus the defining module must be importable in the unpickling environment, and the module must contain the named object, otherwise an exception will be raised.

So it was ultimately unnecessary to create a custom function loading mechanism to load the function into the interpreter as pickle was already doing the same thing (oops!).

This means that there's no discernable performance benefits in my Runner implementation over InterpreterPoolExecutor.

How should we use interpreters then?

In short just use InterpreterPoolExecutor.

with InterpreterPoolExecutor() as executor:

executor.map(function, args)

# or

executor.submit(function, single_arg)

executor.submit(function, single_arg)

...

Results can be accessed easily via futures. The standard lib also provides some basic way to synchronise futures via wait or as_completed

Asyncio

What if you need more complex synchronisation? We can run Executors in asyncio using loop.run_in_executor(...).

with InterpreterThreadPoolExecutor() as executor:

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

await loop.run_in_executor(executor, function, argument)

here's an example using the excellent asyncio.TaskGroup:

async def to_coro[T](aw: Awaitable[T]) -> T:

return await aw

with InterpreterPoolExecutor() as executor:

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

async with asyncio.TaskGroup() as tg:

for _ in range(runs):

# NOTE: a task must be created from a coroutine, run_in_executor returns an `asyncio.Future`

tg.create_task(

to_coro(

loop.run_in_executor(executor, function, argument)

)

)

What about aiointerpreters?

I'm hoping by this point, I've successfully convinced you that aiointerpreters is redundant and the standard library functionality is enough.

I can now safely say that I'm wrong about the out of the box usability of InterpreterPoolExecutor. That being said I don't feel too silly making those mistakes.

With subinterpreters still a very new and niche feature, there are still a lot of sharp edges. One thing that led to my confusions is that there are not many resources on how it works, there are some difference between the information from the PEP and the final implementation. So I do hope the details I share here can save people some time.

As for aiointerpreters, going forward the focus will be more on enhancing the features the standard library offers rather than completely reinventing the wheel (again). This process is already underway ...

InterpreterThreadPoolExecutor

As I've been going through the code in the standard library I've discovered that the current executor implementation is written on top of ThreadPoolExecutor. Once a task is given to a thread it then get's sent to an interpreter within the thread.

This gives us an opportunity to create a hybrid executor that can dispatch to an interpreter conditionally. I created InterpreterThreadExecutor:

from aiointerpreters.executors import InterpreterThreadPoolExecutor, interpreter

with InterpreterThreadPoolExecutor() as executor:

executor.map(interpreter(cpu_bound), (argument for _ in range(runs)))

executor.map(io_bound, (argument for _ in range(runs)))

When the user want to request a dedicated interpreter they simply need to wrap the function in the interpreter decorator.

I think this makes a lot of sense as threads and interpreters both have their trade offs. Interpreters are isolated and allow parallel memory access but passing arguments needs a lot more care and could be slower. On the other hand, threads (GIL enabled) cannot run cpu bound code in parallel.

We could create 2 thread pools but I think it's a lot easier and resource efficient to maintain a single thread pool.

This is particularly useful for asyncio.to_thread():

We can set the default executor at a loop level:

asyncio.get_running_loop().set_default_executor(InterpreterThreadPoolExecutor())

And then whenever we call to_thread the correct executor will be chosen based on what the user specified.

async with asyncio.TaskGroup() as tg:

tg.create_task(asyncio.to_thread(interpreter(cpu_bound), argument))

tg.create_task(asyncio.to_thread(io_bound, argument))

More complex Executors and Runner

Whilst the default aiointerpreters.runner.Runner is a little redundant now, it doesn't mean there are no need for making custom versions of Executor or Runner. There is no one size fits all solution to concurrency and parallelism, so there's plenty of opportunity to create different versions of Executor that behave differently and solve different problems that the user face.

I'm currently working on a Runner that distributes async tasks to coroutines running in separate interpreters similar to aiomultiprocess.

There's also opportunity to take advantage of prepare_main in an executor to reduce the number of copying required.

Finally, running an executor and integrating it with asyncio is not always straightforward, and I'm sure there's some interesting abstractions that can be created on this front.

Closing words

Apologies if this all reads like a massive dump of information, I've realised how tricky the subject of concurrency is and I found that it's important here to provide the most accurate details.

True parallelism in Python is nascent and there simply isn't an obvious way to do things right now and maybe there never will be. With that comes some difficulty in knowing what do do. The most crucial thing here is to get your hands dirty and try different things for yourself and slowly a clearer understanding will form.

p.s. If you're more interested in free-threading, please look at Python 3.14: State of free threading and How free are threads in Python now? my opinions on it have largely remained unchanged.